For so many years, whether it was Talmud and Halacha in my late teens and early twenties at the Orthodox yeshiva, Kerem B’Yavne, or later at the Bible department of Hebrew University, study for me was always based around text. Letters that come together into words, words that put out ideas formed into paragraphs, chapters and then books. Earlier biblical verses augmented upon and interpreted by later passages, in the various strata of rabbinic, medieval and finally modern literature, all wishing to explain and expound upon all that preceded.

A major part of my adult life has been studying, teaching and sharing these Jewish texts with anyone who has been inclined to join me. I was very much part of the “Back to the Sources” when running the education program at Camp Ramah, California, in the 1980’s and what was known later in Israel as the “Jewish Bookshelf” movement. In my personal progression as a Jew, these texts were at first a source of authority holding instruction for how to act, feel and believe. With time, I found that it made far more sense to view them as possible sources of inspiration.

But during all this time, the “Jewish sources” I was dealing with, were the kind you read in a book or on the screen of a computer. Study and teaching meant words, sentences, paragraphs and chapters.

Then, in 2002, I met William Gross. I was considering a move down to Tel Aviv and working with the Masorti congregation Tiferet Shalom. Bill and his wife Lisa were not terribly active members, but they had a huge living room and that’s where many of the congregation’s meetings took place. The first thing you notice in the Gross apartment is the art. There are beautiful works that have been fashioned by Lisa from recycled objects, paintings and fabric wall hangings. But what really stands out are case after case filled with Judaica – Jewish ritual objects – from all over the world. Truth is, during my first meeting there, I paid much more attention to all the silver and brass objects than I did the words being spoken.

William collects just about everything “Jewish”. Not just the mostly metallic items encased in the living room, but books, manuscripts, ketubot, textiles, paper and even bottles of magical water blessed by Kabbalistic rabbis.

William not only collects, but he – a Harvard graduate in History – knows a lot about the things he collects: The type of materials used, the dates and places where these things were created, sometimes even the exact tower after which a particular spice box in his collection was modeled.

It was William who opened my eyes to the fact that there are many different types of sources from which we draw inspiration regarding our lives as Jews and that not every idea, feeling or belief can be described by words.

During my seven years working with William in Ramat Aviv we constantly taught together on a wide variety of topics. He would bring the objects themselves or at least project their images on a screen. I would hand out and read together with our audience. Our goal was to teach a kind of Torah with a relevant message while utilizing objects that had been intended for use. Sometimes we actually used these ritual objects in our synagogue, sometimes just handed them around the circle of young people or adults who had come to the Gross home. Both objects and texts came alive when combined with one another.

It was through Bill that I learned that my definition of “source” was far to narrow and that so much of what we might learn and how we might grow can come from wordless artifacts.

Almost a decade ago, one of William’s friends, Benny Zucker, himself a collector of Judaica, suggested to me that combining the Gross collection, William’s knowledge of art and history and my own book-learning would be a good idea for a weekly Parshat Hashavua site. It’s taken me until now to find the time and I’ve begun experimenting with this over the last few weeks.

I’ve been sifting through thousands of images that William has on file and sorting them according to the weekly Torah reading. Once I’ve found a particular image that catches my eye, I try to let the picture inspire how I might view the biblical text and interpret it in what seems at least this year to be a relevant way.

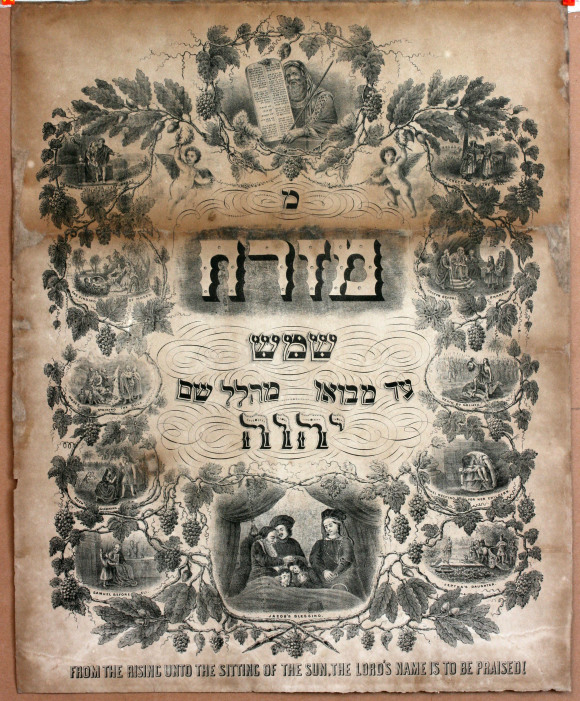

For example, let’s take one of the images I put up on the blog last week:

William has taught me that this a poster, what’s known as a “Mizrah”, an object that one might hang on the eastern wall at home or in a Sukkah to know in which direction to pray. Although it was done in the Turkish style of Moshe Mizrahi, a well-known Iranian Jew who lived in Jerusalem in the beginning of the 20th century, this 59.5cm x 44cm poster was printed in Warsaw, Poland by the Concordia printing-house around 1910.

The theme of the poster is Akeidat Yitzhak, or the Binding of Isaac (Gen 22) and this is what is depicted in the two larger panels with white background. But the bottom panel illustrates another episode in Isaac’s life, that appears in this week’s Torah reading, when Abraham’s servant (named Eliezer in the midrashic tradition) is sent to find his masters beloved son a wife.

Abraham’s servant had already asked God’s guidance in finding the right woman:

“Here I stand by the spring as the daughters of the townsmen come out to draw water; let the maiden to whom I say, ‘Please, lower your jar that I may drink,’ and who replies, ‘Drink, and I will also water your camels – let her be the one whom You have decreed for your servant Isaac. Thereby shall I know that You have dealt graciously with my master”. (Gen. 24:13-14)

And sure enough, the first woman who approaches the spring, was Rebekah, from whom he requested to drink.

“Drink, my lord,’ she said, and she quickly lowered her jar upon her hand and let him drink. When she had let him drink his fill, she said, “I will also draw for your camels, until they finish drinking.” (vs. 18)

Here’s a close up of the act that has just been described:

Perhaps you too have always imagined this scene playing out a little differently. The impression I get from the (not so) young Rebekah is one of a woman who has taken charge of a situation. It even seems as if Abraham’s servant – the one she calls “master” is being forced into drinking, or drinking a bit more than he was ready for. It looks to me that the illustrator (whether original or copied from an earlier piece) is foreshadowing will eventually play out in Rebekah’s life. Pay attention carefully in the weeks to come and you’ll find that her future husband, Isaac is one of the Bible’s most passive figures.

This assumed, or projected, intention of the artist makes even more sense to me when compared to another illustration of this scene:

Perhaps it’s just the style and form of this artist’s drawing tradition, but it seems to my eyes as if both figures are much more relaxed here. It seems – at least at a distance – that Rebekah is a little more gentle and that Abraham’s servant, his hands clasped behind his back, is a little more comfortable drinking from Rebekah’s pitcher.

This close up is also take from a Mizrah, though a far rarer example, coming from the United States sometime around 1880. According to William, this 54.5cm x 44 cm lithograph, was created for both Jewish and Christian use. Our scene is but one of twelve depicted here.

These two illustrations depict a small detail in the narrative in very different ways thereby offering us yet two more ways of understanding a contemporary issue – matchmaking. Abraham’m servant was sent to find a good match for his master’s son and this was a test to try and find out just what kind of person Rebekah might be. How often do we find ourselves thinking about fixing up two single friends with each other with no reason other than that they are both our friends. We love them and want them to be happy. But have we really given much thought to what each might need from and what each might give to, the other?

Both William and I hare happily married to two wonderful women, Lisa and Sascha, but we have found over the years that each of us wish to grow and learn. We each bring something different to the table. I hope you find this inspiring!

Shabbat Shalom

Eye opening explication by using both text and image.

David, I am so happy you and Bill are doing this. I will use your commentary as I prepare my hevrutah study. With love and gratitude, Sally

Okay, I know I’m behind a few weeks – but I was a bit busy the weekend of November 15th when Parashat Hayey Sarah was read – as it was my children’s B’nei Mitzvah… This is a beautiful post and resonates with me on so many levels. I have had the privilege of visiting the Gross family “living room” – it does transfix and transport one to many different times and places. David, using the precious art as “text” you have moved beyond the literal…your interpretations and ideas are inspired. Thank you. – Betty

When I thought about Jewish art, I used to think about Chagall, and my mind stopped there. This opens a new window for me. Just as song animates the Hebrew language, this makes me think about how art illuminates the written word in Judaism.

For me, this is a moving introduction to the role of art in Judaism. Just as song animates the words of the Psalms, art amplifies the stories and states of consciousness that we study.