It’s been almost 40 years since I moved to Israel. As an 18 year old, it was a no brainer. I’d been raised in a Zionist home, educated in a Zionist leaning synagogue, youth movement and summer camp. I had read Leon Uris’ Exodus and Meyer Levin’s The Settlers, had spent a full year of high school living at the youth village Givat Washington and had been accepted to Yeshivat Kerem B’Yavne, the first seminary to combine Torah study and service in the Israeli army. It was to be a one-way move, from Los Angeles to Israel.

Like many, I grew up with terms like “chosen people” and “promised land” which as a young person I associated with the story told in this week’s Torah portion. God commands Avram to leave the land which he called home and go to an unknown destination where God would bless him and grow his family into a great nation. His offspring would grow into a special and chosen people who were promised a special and chosen land.

There is much to be said about what I was told, or not told, about who inhabited the land before our ancestors arrived on the scene and what kind of story those people might have told. Likewise, concerning what I was told and not told concerning who inhabited the land before the first Zionist settlers arrived on the scene at the end of the 19th century and how those people have told and continue to tell their side of the story. But I leave that for another time.

Right now I’m thinking about what I might have lost in my youth by adhering to, and acting upon the belief, that the Land of Israel was, is and will be the only proper place for me, as a Jew, to reside. Did I miss out by being stationary for so many years?

Don’t get me wrong, I have been, I am still and will always support the idea and reality of a Jewish homeland here. I have helped to build and preserve the Zionist vision for almost all of my adult life until now and it is hard for me to conceive of a rich Jewish identity anywhere I might end up living around the world without an ongoing and vibrant relationship with the State of Israel.

But for many years I, like many other former “classical” Zionists, have felt that the collective Jewish enterprise must always consist of voices and experiences from all over the globe. This is not just because there are those whom for whatever reasons will not move to Israel and that they deserve to be heard. It is also in order for our ethnic and spiritual tradition to thrive, each and every Jewish expression from around the world needs to be heard, seen and felt.

And there is something to be said for being in a state of movement, not being entirely sure all of the time that you are in absolutely in the special and chosen place.

Aside from the more famous tale of God commanding Avrami to leave for the promised land there is a somewhat less discussed and contemplated narrative that tells of a regional war in which initially Avram plays no part. It seems that this story made itself into the book of Genesis only because toward the end, Avam’s nephew Lot was taken captive. It is then that we read, “a fugitive brought the news to Avram the Hebrew” (Gen. 14:13).

This is the first time that Avram called “the Hebrew”, or ha’ivri. The etymology of this title is debated by the rabbis in the 2nd century:

Rabbi Yehudah says: the entire world is on one side (ever), while he is on the other side (ever);

Rabbi Nehemiah says; he is descended from Ever (grandson of Noah);

The Rabbis say: He was from the other side (ever) of the river and he spoke in the Hebrew (ivri) language. (Midrash Bereshit Rabbah 42:8)

According to the first view, the title “Hebrew” takes on an existential meaning and refers to the theological revolution ascribed to Avram by casting him (and those who will be called by this name) in an adversarial position with the surrounding polytheistic culture. The second seems purely genealogical, though in rabbinic literature, it is this particular ancestor who is credited with setting up the first house of study. The third view gives two reasons, one of them a bit tautological (Avram is called a Hebrew because he spoke Hebrew but the Hebrew language could just as well be named after Avram, the nation’s founder, who bore the title Hebrew). The other, ostensibly geographical in nature, echoes an explanation already found in the Bible itself. When Joshua assembles all of Israel at Shchem to renew their covenant with the Lord he begins:

In olden times, your forefathers … lived beyond (m’ever) the river and worshipped other gods. But I took your father Avraham from beyond (m’ever) the river and led him through the whole land of Canaan … (Jos. 24:2-3)

This interpretation is based on the meaning of the root EV”R, as in to pass from place to place, and, at least on the midrashic level, leads to the quintessential Jewish trait of wandering. True, for many, the Jewish State was an attempt to put an end to this wandering, and indeed for many that has become the case. But there is something to be said for assuming – at least from time to time – a state of ongoing exile. I mean this in a good way, in a way that one views one’s existence as being a constant negotiation with the world around, encouraging growth and improvement, and not getting stuck in one place.

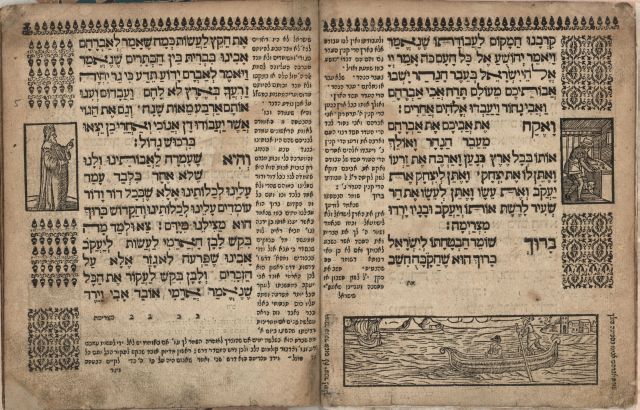

The images shown here – each from the pages of century old Haggadot – are based upon this last interpretation, albeit in a somewhat naïve manner. The title Hebrew here is understood as one who has moved from one side of the river to another. I doubt if the first printer who juxtaposed this image to the verse from Joshua thought of the guy with the paddle in the little boat as God. He simply used a picture that was easily available to him.

But the message is clear – Avram is on the move. It might be that he’s moving from one side of the river to the other, or perhaps he’s even moving up-stream or down-stream for a while, enjoying the ride. But moving he is and perhaps this is an important part of celebrating his legacy.

Shabbat Shalom

Sometimes I wonder what would have happened if my plans to make aliyah hadn’t been derailed.

Would my vision of Israel be stronger or weakened by the experiences I might have had? Impossible to say but often wonder if Israel is big enough for our people or if we are too small.

That global perspective you talk about becomes more valuable to me each year and I wonder if I am being the best father I can be.

Am I providing too much guidance or not enough to my children?

Is Lech Lecha to be taken literally and am I falling down on my obligations by not making plans now to at least go back to Israel?

Or am I doing my part by taking the paths I have chosen and seeing where they lead.

Good post today, I very much enjoyed it. Lots of food for thought.

A rich teaching of the gift of a chosen land and the value of movement. The illustrations add authenticity to the words.