A major theme in the book of Genesis, which we finish reading this Shabbat, is that the younger son is usually preferred over the older, first-born: Cain/Abel, Isaac/Ishmael, Jacob/Esau, Judah/Reuven, Zerah/Peretz and, as we’ve read over the last few weeks, Joseph/Jacob’s other sons. So it’s not surprising when Jacob, who is about to bless Joseph’s sons and intentionally favors the younger, Ephriam, over his older brother, Manasseh.

Now the eyes of Israel were dim with age, so that he could not see. So Joseph brought them near him, and he kissed them and embraced them. And Israel said to Joseph, “I never expected to see your face; and behold, God has let me see your offspring also.” Then Joseph removed them from his knees, and he bowed himself with his face to the earth. And Joseph took them both, Ephraim in his right hand toward Israel’s left hand, and Manasseh in his left hand toward Israel’s right hand, and brought them near him. And Israel stretched out his right hand and laid it on the head of Ephraim, who was the younger, and his left hand on the head of Manasseh, crossing his hands, for Manasseh was the firstborn. (Gen .48:11-14)

There are different ways to show who is who when it comes to illustrating this story. In the picture below, younger brother Ephraim is shorter, wearing a simpler garment then his brother and displaying body language that would hint to less maturity. This image, taken from a 1846 edition of Tzena Urena (of which I wrote last week), translated into French by A. ben Baruch Crehange. The lithographs in the book were done by Haguental & Fagonde, and so far, I’m not able to tell whether they are original art done for this edition or whether they are copied from some other source. In any case, they are unlike the illustrations one usually finds in the Yiddish editions of Tzena Urena.

La Semaine Israelite (French version of Tzena Urena), Paris, France, 1846, Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv

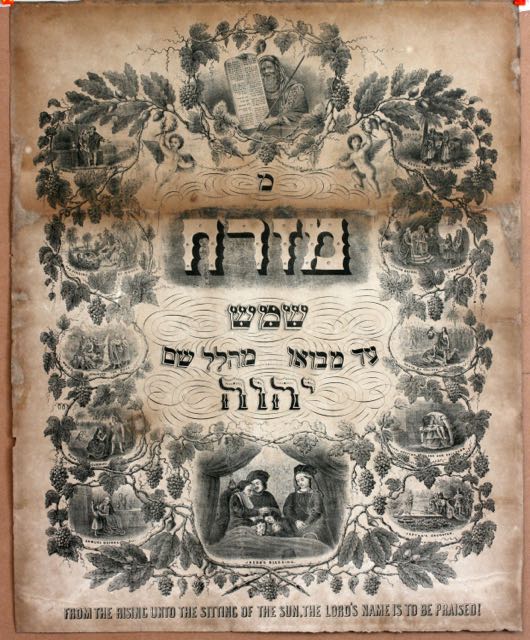

What I like most about this picture is how it accentuates the age difference, thereby focusing on the message of the text. Less so in this image from a Mizrah printed in Germany around 1860, in which the boys seem to be same age.

But this may very well be meant as a picture of another scene in this week’s Torah reading, that which is often called “Jacob’s Blessings” (Gen. 49) in which the father has a prophetic message for each of his sons, though not all of them positive in nature. In any case, this is what the title of the picture says. There are a number of rather similar Mizrai posters that were printed in the area of France and Germany in the mid 19th century and it seems hard to know which of them preceded the others. Note that here, one of the most important features of the literary account – Jacob crossing his hands – is missing. One might speculate that other, possibly latter, printers thought that the picture should match the title they understood as referring to Gen. 49 and so we find these two examples:

Here it seems as if the brothers were competing for space in front of their father.

In this picture, it looks as though Jacob is blessing each of his sons while the others patiently wait their turn.

Mizrah posters were found in the United States as well.

This item is unique in a number of ways. Being printed in the US, possibly for use by Christians as well, both Hebrew and English are used. There are many images of biblical stories, yet (unlike the European examples) the image of Jacob blessing Ephraim and Manasseh is central. Finally, only in this image does Joseph’s wife, Asenath, appear:

The mother of the boys, who is missing from this scene, both in the biblical text and in every other image I’ve seen until now, is portrayed as a woman of modest dress and demure with hands folded in her lap. While the Torah mentions Asenath three times, there is no description of her other than “daughter of Potiphera, priest of On”. In the apocryphal Joseph and Asenath (chap. 22) as well as in the midrashic tradition (e.g. Pesikta Rabbati 3), there is mention of her part in Jacob’s blessing of her children, but otherwise the book of Genesis is silent on this.

As much as I would like to think that our artist was well versed, or at least well informed by others, in early Jewish literature, the picture above has been copied from Rembrandt’s “Jacob Blessing the Children of Joseph”:

I don’t know if he was the first artist to add Asenath to the scene that begged her presence, but he has certainly done more than others to bring this to light. For far too long, women were “left out of the picture” and in the scheme of Western culture, Rembrandt helped rectify this.

Who are the missing persons in our stories? When do we take credit for something done by others? When do we “borrow” someone else’s story and make it our own? These are the questions that have been occupying my attention over the last few weeks and I expect that they will continue to do so. After all, finding the missing persons in one’s life-story is an important part of making this a better world. And finding the missing stories of one’s life is an important part of becoming a better person.

Shabbat Shalom