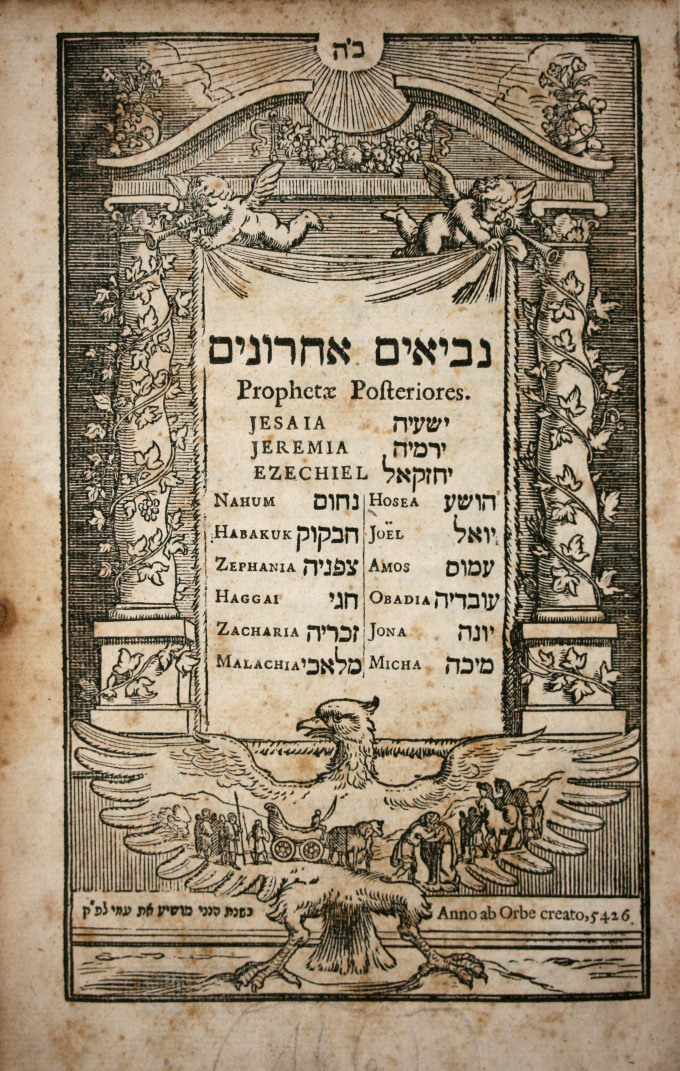

I have only now discovered a Hebrew language blog, Am Hasefer, where Rabbi Avishai Elbaum has posted another wonderful image of Jacob’s meeting with Joseph. This image, inscribed on the background of an eagle, is found on a number of title pages from different books printed by different publishers in cities like Amsterdam, Berlin, Frankfurt, and Prague. As often happens with images used over and over again, in books published later, they appear lighter-toned and far less defined than in the earlier examples.

There are a number of books in the Gross Family Collection with this image on the title page, but by far, the most beautiful example is from a Tanach, Hebrew Bible, published by Joseph Atias in Amsterdam in 1667:

As Rabbi Elbaum explains, the picture shows Jacob, his sons and animals on the right, embracing Joseph, whose chariot and soldiers are on the left, with a spread-winged eagle in the background. The eagle (Moshe Ra’anan has more on this at another Hebrew blog which is dedicated to the daily study of a page of Talmud), according to Elbaum, symbolizes the foreign kingdom under which the people of Israel are protected, and under which this meeting between father and son is protected, and hints to the future salvation from slavery. Rabbi Elbaum is, no doubt, referring to God’s words to Israel after the exodus from Egypt: “You yourselves have seen what I did to Egypt, and how I carried you on eagles’ wings and brought you to myself.” (Ex. 19:4).

An anonymous commentator on the Am Hasefer blog writes that he had always been under the impression that this image depicted a different story from the book of Genesis, that of Jacob’s meeting with his estranged brother Esau (Gen. 33). Rabbi Elbaum justifies his interpretation by pointing out that the chariot in the picture, mentioned specifically in the Torah’s account of Jacob meeting Joseph, is missing in the story of Jacob meeting Esau.

It seems however that the anonymous commentator was partially correct in that the central figures in the picture were, at least at first, those of Jacob and Esau. My friend and teacher William Gross has brought this picture to my attention:

The picture appears in an English bible, which was published in Cambridge in 1675 using the illustrations first published by Mattaus Merion of Basel in 1630. This picture appears on the pages corresponding to the story of Jacob meeting his estranged brother Esau (Gen. 33). So it seems that at some later date, an artist added the chariot on the left and the animals on the right, thereby adapting the picture to the story of Jacob meeting Joseph.

Finally, I will add that it seems to William and me that the modified picture was used (or even created by) the publisher Joseph Atias for two reasons: First, quite often one finds an image of the publisher’s, or author’s, biblical namesake, on the title page – in this case, one of the most dramatic moments in Joseph’s life; Second, Atias who was born in Spain in the beginning of the 17th century and had fled to the safe haven of Amsterdam, very possibly thought of the verse in Exodus, “…how I carried you on eagles’ wings and brought you to Myself.” (Ex. 19:4) as relevant to how he and his family were saved from oppression in Spain.

The complex history of the use and reuse of these images in the printing of sacred literature as discussed above and in my post of last week has much to teach us about how we tell stories. We retell, embellish, borrow and redirect images and themes, adapting to the situation at hand. The more we understand how this was done in the past, the better we are able to understand our own lives and the lives of others around us.

David, I so appreciate what you and Bill are doing. This week’s hevrutah focused on Vayigash and Luke 3, and the themes of repentance found in both of these texts. Your work is enriching our study. Sally