We all tell the story differently. Whatever it was that happened to us or whatever it was that we observed happening to others, each of us gives a slightly different account. Think of how each of the characters in the Joseph saga would have told the story – Joseph, Judah and Jacob – each with their own distinctive version of the events reflecting their own distinctive experience.So too when it comes to the telling and retelling of the entire biblical narrative. Each teacher, commentator and preacher will put their own personal imprint on the story.

Over the last few months, I have been attempting to further my own education with regard to Jewish art, especially when it is presented in order to help retell the biblical narrative. This week I turned to one of the most widely published Jewish books in the last four centuries – Tzena U’rena. Over 200 different editions of this book written in Yiddish by R. Jacob ben Isaac Ashkenazi of Janow (16th century, Poland) have appeared in Central and Eastern Europe.

There are 22 different editions of Tzena Urena in the Gross Family Collection and of those, 12 are illustrated. In most of these, a caption above the image reads (in Yiddish) “Jacob goes out of the Land of Canaan to the Land of Goshen with all of his children and grandchildren and his animals/cattle”. The interesting (and for me, somewhat confusing) thing is that most of those illustrations are different.

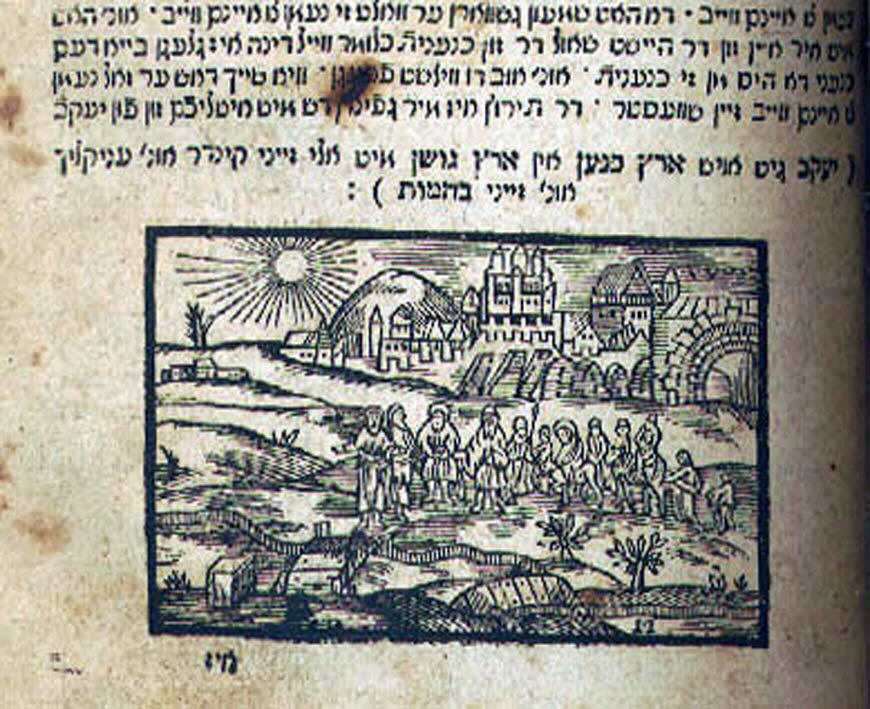

The most common is this one that shows 12 individuals, 2 riding on donkeys, with a great walled city in the background and a river with at least 2 bridges in the foreground:

With a certain stretch of imagination, one might suppose that the 12 figures in the picture symbolically portray Jacob and his 11 sons who are setting out from Canaan, or arriving in Goshen. And although “his animals” are covered at least in principle by the two donkeys, it is far more plausible that this picture was merely a “rough” match for the text and was “close enough” as far as the printer, or publisher, was concerned.

But the history of this particular image is a bit more complicated since it is known to us from a different context, the exodus from Egypt, as found below in this well-known Haggadah published in Amsterdam in 1695:

The caption below the picture reads (in Hebrew): “And the Israelites journeyed from Raamses to Sukkoth…” (Ex. 12:37). And even more complicated is the fact that this picture was inspired by an earlier tradition of illustrations made by Mattheus Merian of Basel, his son and apprentices for Christian Bibles in the 17th century.

A far more surprising choice is what appears below:

As in most of the editions, the caption above this image (actually at the bottom of the previous column) reads “Jacob goes out of the Land of Goshen …”. But for some unknown reason, the publisher chose a depiction of the monthly blessing of the moon – kiddush levana – ceremony, the type of illustration well-known from Customs Books.

Perhaps equally surprising is a picture of what is found in this edition 1796 edition from Sulzbach.

The picture is obviously a somewhat simpler copy of another illustration from the Amsterdam Haggadah of 1695, which in turn was inspired by Merion’s artwork, this one depicting the Temple in Jerusalem:

Apparently, the publisher of a much later version of Tzena Urena solved this discrepancy by adding Joseph (with his people on the left) greeting his father Jacob (with his people, and animals, on the right).

There are still a number of other illustrations in the various editions of Tzena Urena in the Gross Family Collection which are not very clear, though closer to what we might expect to see in this context. My favorite was printed in Sulzbach circa 1770.

This may not be the most sophisticated of the illustrations appearing in this week’s Torah portion as found in the different editions of Tzena Urena, but it seems best matched to the caption and context: The man in the foreground on the right with turban and shepherd’s staff is clearly the leader and presumably Jacob; a younger man to his left, would be Judah, walking along with all the “children and grandchildren”, as well as with many animals.

My friend and teacher, Prof. Shalom Sabar, tells me not to take these pictures very seriously since it is clear from this and many other examples that the art in Tzena Urena, was copied from other books and contexts in a rather careless fashion. And while that may be true from the standpoint of Jewish art history, I discern a message in the madness: When telling stories, we quite often reuse and recycle descriptions and themes from other entirely unrelated stories. One might try to be more aware and cautious of this, but we can’t entirely help it. We’d do well to remember this both when telling a story and when listening to those told to us by others.

Shabbat Shalom